How to not over wind a table clock safely ?

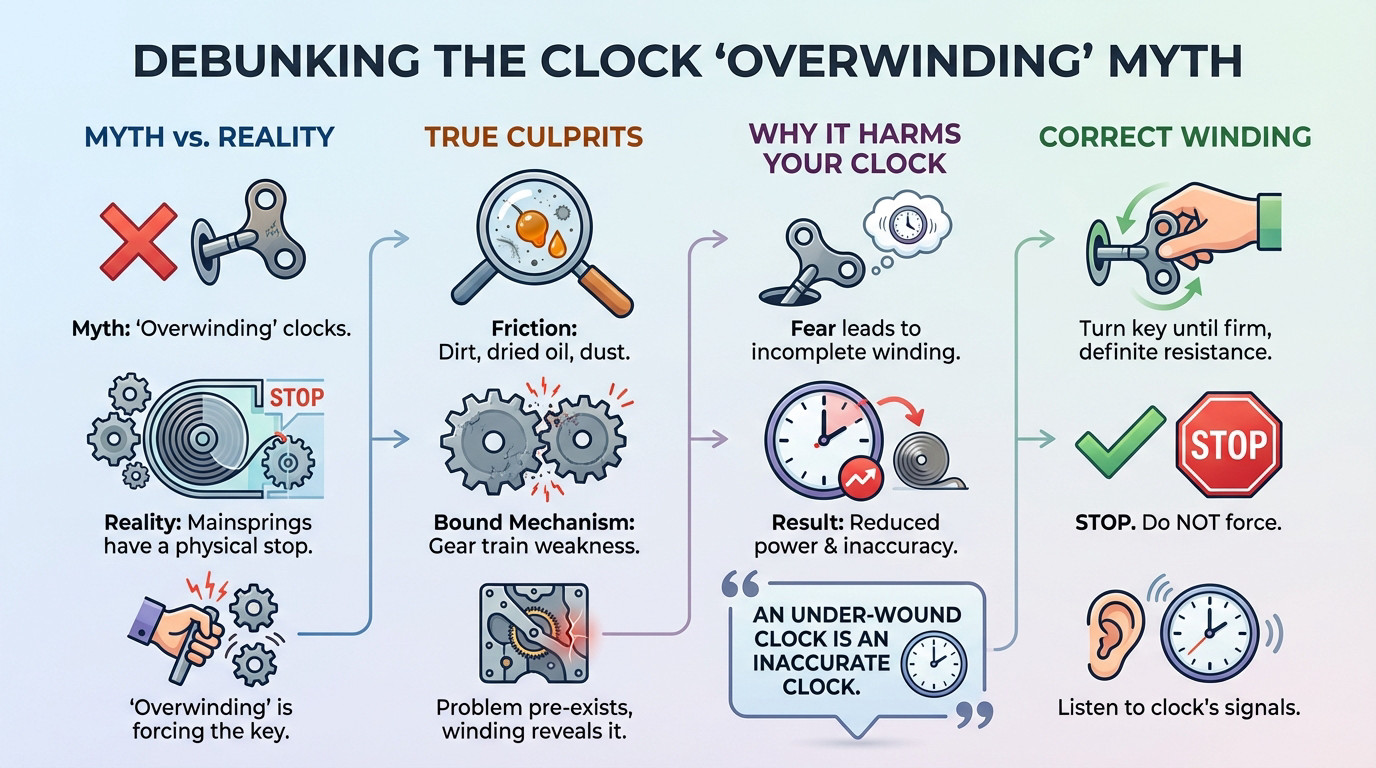

The concept of "overwinding" is a myth, as mainsprings are mechanically designed to reach a definitive physical stop. Avoiding full winding actually reduces timekeeping accuracy. Instead of fearing the key, wind until a solid resistance is felt, understanding that a stuck clock usually signals a need for maintenance rather than a broken spring.

Many collectors hesitate to fully power their heirlooms for fear of snapping a spring, yet learning how to not over wind table clock mechanisms is actually about trusting a distinct physical limit. We debunk the persistent myth of overwinding to reveal that the real issue is often neglected maintenance, explaining exactly why your key stops and what that resistance truly means for the movement. By mastering the subtle sensory cues of a fully wound barrel, you will confidently maintain your timepiece's accuracy without ever risking damage to the delicate internal gear train.

- The Overwinding Myth: What Really Happens When You Wind Your Clock

- Inside the Mechanism: Understanding the Physical Limits

- The Art of Winding: Developing Your Sensory Cues

- Red Flags: When the Chime Train Is Telling You to Stop

- A Practical Guide for Different Table Clocks

- Your best defense is a good maintenance routine

The Overwinding Myth: What Really Happens When You Wind Your Clock

Let's Be Clear: You Probably Can't 'Overwind' Your Clock

Let's kill this myth right now. Your clock's mainspring is engineered with a definitive physical stop. It isn't a polite suggestion; it is a hard mechanical limit you hit.

When people claim they "overwound" a clock, they usually mean they used brute force. The issue isn't taking one turn too many; it is forcing the key past that natural resistance. You are fighting physics, not the time.

The real danger isn't filling the tank. It is ignoring the tactile signal your clock sends when it is full.

The Real Culprits Behind a 'Stuck' Clock

So why does it stop? Usually, it's friction. Years of dust and dried oil inside the movement create a sticky mess. This gunk prevents the spring from releasing its power.

Sometimes, you have a bound up mechanism. When the spring is at maximum tension, it puts pressure on the gear train. If there is a weak tooth, it jams.

Here is the kicker: the problem was already there. Fully winding the clock just exposed the issue. You didn't break it by winding; you just discovered that a lack of maintenance finally caught up with you.

Why This Misconception is Dangerous for Your Clock

The fear of breaking things makes owners timid. They stop winding too early. This reduces how long the clock runs and, worse, destroys its ability to keep time accurately.

Once you understand this, you can treat your antique right. The goal is to not over wind table clock mechanisms by respecting the stop, while still giving them full power.

So What Does It Mean to Wind Correctly?

Correct winding is about feel, not counting turns. You turn the key steadily until you hit a resistance firm and definitive. That is the wall. Stop there. Do not push past it, but don't stop before it.

Now that you know the mechanical limits, we need to look closer. The next sections will dig into the specific sensory cues so you never second-guess that stopping point again. It’s easier than you think.

Inside the Mechanism: Understanding the Physical Limits

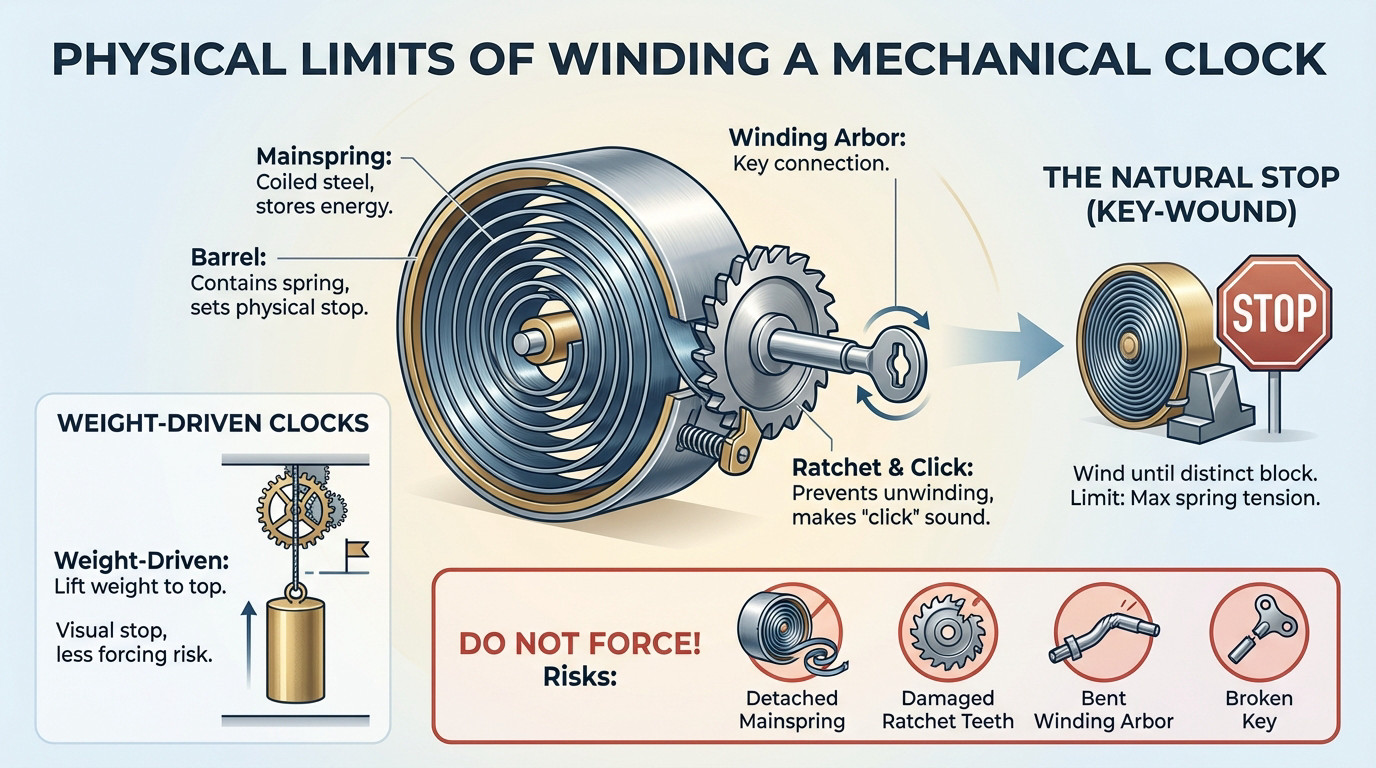

The Heart of the Matter: The Mainspring and Barrel

Think of the mainspring as a long, flat ribbon of tempered steel tightly coiled inside the movement. It acts exactly like a battery for your timepiece. Winding it simply stores potential energy to drive the gears.

The barrel is the cylindrical housing that keeps this spring contained. As you wind, the steel coils tighter and tighter around itself until it physically cannot squeeze any further. That solid wall of resistance you feel is the natural stop.

Picture a tin can packed to the brim with material. Once it is full, it is full. Insisting on pushing more in is futile.

The Unsung Heroes: Ratchet, Click, and Winding Arbor

The winding arbor is that sturdy metal shaft where your key fits. It provides the direct physical connection between your hand and the internal engine, transferring your force into the mechanism.

Then you have the click and ratchet wheel system working in tandem. This duo creates that satisfying "click" sound and acts as a brake to stop the spring from violently unwinding backwards.

- The Mainspring: The power source, a coiled steel spring.

- The Barrel: The cylindrical case containing the mainspring.

- The Arbor: The shaft you turn with the key.

- The Ratchet Wheel & Click: The safety mechanism that allows winding in one direction only.

Key-Wound vs. Weight-Driven: Not All Clocks Are the Same

We need to focus on key-wound clocks because that is where the danger lies. The stopping point is defined by the mainspring's maximum tension. Learning how not over wind table clock springs means respecting that sudden, hard block you feel.

Weight-driven clocks operate on a completely different principle. You pull a chain or cable until the weight hits the top plate. The limit is visual and obvious, so the risk of accidentally forcing the mechanism is practically non-existent compared to spring-driven counterparts.

The Risk of Forcing Past the Natural Stop

Here is what happens when you ignore the resistance and force the key. The pressure doesn't go into the spring; it attacks the hook anchoring the spring to the barrel. You risk tearing the spring right off its internal mount.

It gets worse, as you might strip the teeth off the ratchet wheel, bend the winding arbor, or snap the key. The spring might survive, but the surrounding parts often take the hit for your heavy hand.

The Art of Winding: Developing Your Sensory Cues

Theory is fine, but let's get real about execution. Winding isn't a chore; it is a tactile dialogue with your machine, and you just need to learn how to listen.

Prepare for Winding: A Simple Pre-flight Check

Before you even touch the key, look at the setup. Your clock must sit on a stable and flat surface. If the unit shifts or wobbles while you work, it distorts the physical feedback you rely on to judge tension safely.

Next, verify your hardware. Ensure the key is the correct gauge and fully inserted. A sloppy fit can slip, damaging the winding arbor or mimicking resistance, tricking you into applying force where you shouldn't.

Listen and Feel: The Two Pillars of Correct Winding

Your hands provide the first data point. The winding action must be smooth and steady. Resistance should climb gradually and linearly, never feeling gritty or jerky, which would suggest internal friction.

Your ears provide the second validation. Listen closely to the ratchet's song. The clicks must be regular, crisp, and clear. A muffled click or a sudden change in pitch is a warning sign.

- Feel the tension build: It should be a smooth, gradual increase, not sudden.

- Listen to the clicks: The sound of the ratchet should be consistent and even.

- Respect the final stop: When the key stops, you stop. It will feel like hitting a tiny wall.

Recognizing the 'Full' Point

You need to identify the final stopping point without doubt. It isn't a soft, spongy sensation like you might expect from a modern device. It feels like hitting a solid mechanical dead end where the key simply refuses to rotate further.

Never try to force "just one last click" into the barrel. That extra shove is exactly how not to over wind a table clock. The stop is absolute. Ignoring this hard limit is asking for a broken mainspring or stripped gears.

Establishing a Winding Routine

Make this a ritual, performed at the same time every cycle. If you own an 8-day model, pick a specific slot, like Sunday morning. Consistency is king for mechanical health and prevents memory lapses.

A strict schedule keeps the mainspring operating within its optimal tension range. It also prevents the spring from fully exhausting its energy, which often leaves the clock struggling to restart on its own without professional intervention.

Red Flags: When the Chime Train Is Telling You to Stop

Sometimes, even if you are paying attention, something just feels wrong. Your clock is actually talking to you, and quite often, it is the chime mechanism that screams for help first.

The Canary in the Coal Mine: Your Clock's Chime

Most people don't realize table clocks usually have separate power sources. You have a gear train driving the time and a completely different one for the melody. That chime train is often the more delicate beast of the two. It is intricate, temperamental, and frankly, easier to mess up.

Because of that complexity, it acts as your early warning system. If the melody starts dragging, sounds weak, or stops dead while the hands keep moving, pay attention immediately. That isn't a quirk; it is a serious sign of stress within the movement.

What a Silent Chime Really Means

You wind it up, and suddenly the house goes quiet. That silence usually means the spring coils are binding together from dried grease. The friction is literally locking the power inside the barrel, preventing it from releasing energy.

This is the exact moment where most owners destroy their heirlooms. They think a little extra force will "jumpstart" the mechanism. It won't; you are just tightening a knot that is already impossible to untie without damage.

Other Warning Signs During Winding

Your fingers are better diagnostic tools than your eyes here. You might feel a "gritty" sensation through the key long before it stops. Sometimes, you hit a wall of resistance way too early, or hear grinding sounds like metal chewing on gravel.

These aren't signs that you need to not over wind table clock mechanisms harder. They are desperate pleas for cleaning and lubrication. The clock doesn't need muscle; it is telling you it needs a skilled horologist.

What to Do When You Feel Something Is Wrong

Here is the only rule that matters: stop everything immediately. Do not try to back the key out, and definitely do not try to force it forward another inch.

Step away and let the mechanism sit for a while. Occasionally, the internal tension settles down on its own after a few hours, though I wouldn't bet money on it happening.

If it stays stuck, you have to call a professional clockmaker. Trying to "release" that mainspring yourself is dangerous. You will turn a fifty-dollar maintenance job into a five-hundred-dollar restoration nightmare.

A Practical Guide for Different Table Clocks

Not all clocks look the same. Knowing if you have one, two, or three keyholes changes the game.

One, Two, or Three Holes: Decoding Your Clock's Face

Look closely at the winding holes positioned on your dial. A single hole indicates a time only movement. Two holes control the time and the hour/half-hour strike. Three holes manage time, the hour strike, and a quarterly chime like Westminster.

Remember that each hole connects to a distinct mainspring. You must wind every mechanism until it reaches its individual stop. Never assume they share the same tension limit. Treat them as separate engines powering the gear trains.

The Winding Map: A Comparative Table

Use this breakdown to understand the specific needs of common clock types. It helps you not over wind table clock springs by mistake.

| Clock Type | Winding Hole Function(s) | Winding Frequency | Key Sensory Cue |

| 1-Day Time-Only Clock | Timekeeping | Daily | One mainspring to wind until it stops firmly. |

| 8-Day Time & Strike Clock | Right Hole: Timekeeping (usually). Left Hole: Hour/Half-hour strike (usually). | Weekly | Wind both until each one stops. The strike spring might feel slightly different from the time spring. |

| 8-Day Triple Chime Clock | Center: Timekeeping. Left & Right: Hour strike and quarterly chimes. | Weekly | Wind all three. Pay close attention to the distinct feel of each mainspring reaching its limit. |

| 31-Day Clock | Often one or two holes. | Monthly | Requires more turns. The increase in tension is very gradual, so be patient and attentive until the firm stop. |

Tips for Clocks with Multiple Winding Holes

You should always wind all springs fully during your session. Never wind just one and leave the others flat. This habit keeps the mechanism's internal wear balanced. It also stops you from forgetting one train later.

Springs rarely offer the exact same physical resistance to your hand. The strike spring often feels heavier or lighter than the time spring. You must get used to the distinct sensations of every specific winding hole.

A Special Note on 31-Day Clocks

These clocks rely on massive, powerful springs to run a full month. The winding process demands many more turns of the key than usual. Do not get anxious if it feels like it takes forever. That length is completely standard.

Patience is the only real secret here. Turn the key calmly and regularly. Keep your focus on that building tension until you hit the final stop.

Your best defense is a good maintenance routine

A clean machine is a happy machine

Here is a fact that surprises most collectors: 90% of the issues people blame on "over-winding" are actually caused by a dirty mechanism. Over decades, the original oil inevitably thickens, collects dust, and transforms into a sticky, abrasive paste.

This sludge creates massive friction throughout the gear train. Instead of transferring power smoothly, the mainspring fights this resistance, causing the gears to lock up—often right when you try to not over wind table clock mechanisms but simply wind them fully.

The role of professional servicing

Treat your timepiece like a vintage sports car; it is a complex machine that demands regular professional maintenance to survive. Ignoring this doesn't save money; it just guarantees a breakdown.

I strongly advise scheduling a full service—complete dismantling, cleaning, and fresh lubrication—every 5 to 7 years. Consider this an investment, not a sunk cost. It is the only reliable way to prevent the internal oil from drying out and seizing the movement.

A skilled horologist will spot worn pivots before they grind everything to a halt, saving you from a massive repair bill later.

Simple habits for a long-lasting clock

You don't need to be a watchmaker to extend your clock's life; you just need to adopt a few rigid habits.

- Keep it level and stable: An unbalanced clock puts uneven wear on its components.

- Follow a strict winding schedule: Wind it fully on the same day each week or month.

- Avoid extreme environments: Keep it away from direct sunlight, heat sources, or high humidity.

- Let it run: A clock is designed to run. Storing it for years without running is not ideal for the lubricants.

Don't be afraid to use your clock

Here is the truth: a well-maintained mechanism is incredibly robust. Stop tiptoeing around it. If the maintenance is up to date, you really shouldn't be afraid to wind it all the way up.

Real preservation comes from consistent attention, not fear. So, go ahead. Wind it, listen to that heartbeat, and enjoy the piece. That is exactly what it was built for.

Ultimately, the fear of "overwinding" should not prevent you from enjoying your timepiece. By understanding the mechanism and respecting the physical stop, you can wind with confidence. Remember that a stopped clock usually signals a need for maintenance, not a broken spring. Listen to the resistance, never force the key, and keep your clock clean.

Browse our curated table clock collection for mechanical and quartz options.

FAQ

What does it actually mean when a clock is "overwound"?

Technically, the term "overwound" is a misnomer. A clock cannot be wound too tightly unless you physically break the mainspring or the winding arbor with brute force. When people say a clock is overwound, it usually means the mainspring is fully wound, but the clock refuses to run.

This happens not because of the tension, but because the mechanism is dirty or the oil has dried out. The friction in the gear train has become greater than the power the spring can deliver. The clock isn't broken because you wound it too much; it simply needs a professional cleaning and lubrication to release that stored energy.

How many turns does it take to fully wind a table clock?

There is no universal number of turns, as it depends entirely on the gearing and the duration of your clock (1-day vs. 8-day vs. 31-day). Instead of counting turns, you must rely on sensory cues. Wind the key steadily until you feel a distinct, solid resistance.

A clock mainspring has a physical limit. You will feel the tension increase gradually, and then it will come to a definite stop. Once you hit this wall, do not try to force the key any further. That solid stop indicates the clock is fully wound.

My clock is fully wound but won't run; how do I safely unwind it?

You should never attempt to manually unwind a clock unless you are trained to do so. The mainspring holds a tremendous amount of potential energy. Trying to release the "click" (the safety catch) without the proper tools and grip can result in serious injury or catastrophic damage.

If your clock is wound tight and won't run, the safest course of action is to take it to a professional horologist. They can safely "let down" the mainspring and address the underlying friction issue that is preventing the clock from running.

Can I use WD-40 to fix a stuck clock mechanism?

Absolutely not. You should never use WD-40 or similar household sprays on a clock movement. While it might get the clock running momentarily, WD-40 is a solvent, not a lubricant. It will strip away existing oil and eventually dry into a sticky, gummy residue that attracts dust and dirt.

Using improper lubricants is the fastest way to turn a simple cleaning job into a complex repair. Clock movements require highly specific, non-gumming clock oil applied in precise amounts to specific pivot points.

Why does my pendulum stop swinging even after winding?

If the clock is wound but the pendulum stops after a few minutes, the first thing to check is if the clock is level. Listen to the "tick-tock" sound; it should be an even, rhythmic heartbeat. If it sounds like a galloping horse (long-short-long-short), the clock is "out of beat" and will eventually stop.

If the clock is perfectly level and fully wound but still stops, it is likely suffering from the friction issues mentioned earlier. The mechanism is "bound up" by old oil and dirt, preventing the power from reaching the escapement to keep the pendulum moving.